But international recognition would soon follow; at the 1925 Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes (International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts) in Paris, Wiwen Nilsson was awarded a Médaille d'Or (Gold Medal) for arts and crafts. Gregor Paulsson, the president of the Swedish Society of Crafts and Design and a respected art historian, curated the fair, and would become an important person for Wiwen Nilsson and his recognition in Sweden as well as internationally. Following his success in Paris, Wiwen Nilsson was invited to exhibit in New York at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1926, and from 1926–1928 his works were exhibited at several other important institutions in the USA, including The Minneapolis Institute of Art and The Art Institute of Chicago. During this time his pieces received great acclaim among art critics. With these exhibitions, his international recognition was established, and in the years and decades that followed, his works would be continuously exhibited on the international stage.

Art historian Åke Stavenow wrote in 1926 that “Wiwen Nilsson attempts to launch a purely modernist style ... As with most new styles, Wiwen Nilsson’s pieces have attracted both opposition and recognition.”

Wiwen Nilsson and his work continued to divide opinion in Sweden, but not at the expense of praise and recognition. In 1927, he assumed ownership of his father’s company, which gave him full creative freedom, and in 1928 he was appointed Royal Court Jeweler to the Swedish Royal Court.

It was in 1930 that Wiwen Nilsson’s work became truly lauded in Sweden. At Stockholmsutställningen (The Stockholm Exhibition), his designs garnered critical acclaim, with critics hailing his “spartan disdain” for ornamentation, celebrating the precision of his craftsmanship, and suggesting that Wiwen Nilsson had “driven simplicity to its peak but also to the height of refinement”. It was at this exhibition that Wiwen Nilsson introduced a new cutlery design and jewellery designed with what would become one of his trademark materials – rock crystal. Here, he also introduced the cross in his jewellery designs, which up until this point had been solely a manifestation of Christian faith in Sweden. His jewellery collections were subsequently exhibited internationally, including at Dorland House in London, UK in 1931, the Venice Biennale in Italy in 1934, the Paris World Exhibition in France in 1937, and the New York World's Fair in the USA in 1939.

Wiwen Nilsson’s workshop.

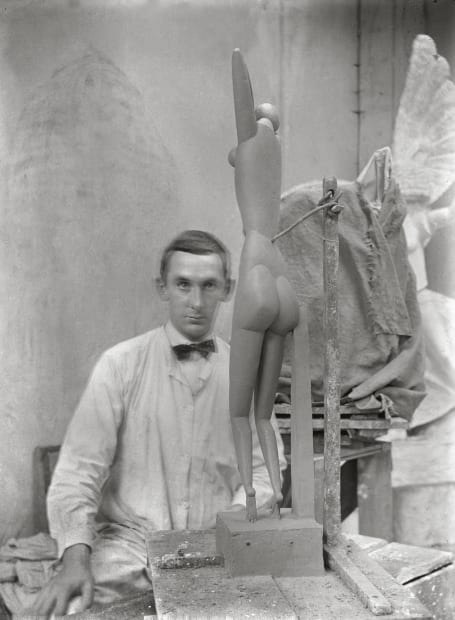

Wiwen Nilsson’s workshop. Wiwen Nilsson sculpting in Arvid Källström’s atelier in Paris, 1924.

Wiwen Nilsson sculpting in Arvid Källström’s atelier in Paris, 1924. Wiwen Nilsson’s workshop.

Wiwen Nilsson’s workshop. Wiwen Nilsson’s workshop.

Wiwen Nilsson’s workshop. Wiwen Nilsson’s workshop.

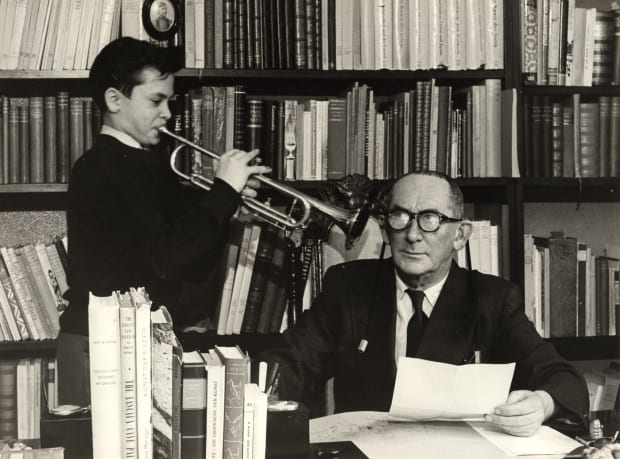

Wiwen Nilsson’s workshop. Wiwen Nilsson and his son, Tore, 1957.

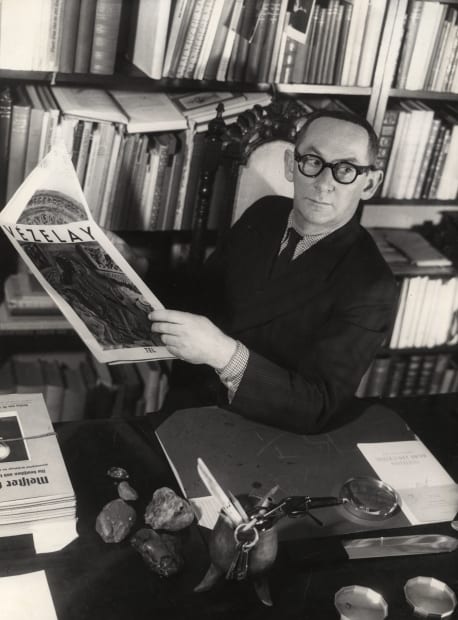

Wiwen Nilsson and his son, Tore, 1957. Wiwen Nilsson at his desk.

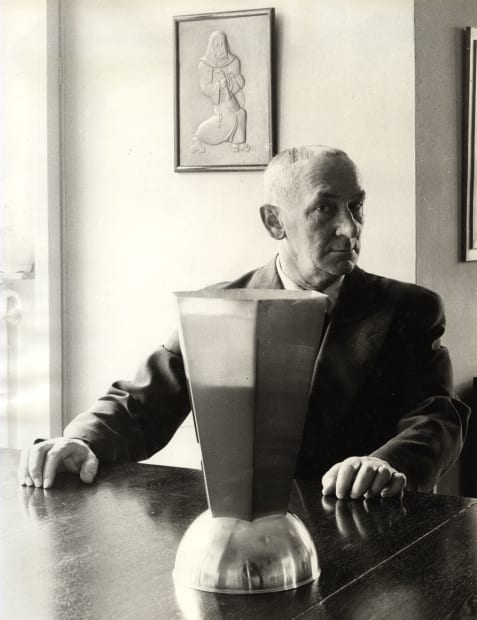

Wiwen Nilsson at his desk. Wiwen Nilsson with a vase.

Wiwen Nilsson with a vase. Wiwen Nilsson outside the shop in Lund.

Wiwen Nilsson outside the shop in Lund. Wiwen Nilsson, 1959.

Wiwen Nilsson, 1959.